It may come as a shock that the story of the first family in the Bible is also the story of the first murder. Or, maybe on month 10 or 11 of a pandemic, it might not be that shocking. Adam and Eve give birth to Cain and Abel. The name Cain means to acquire, possess, or manufacture, like what one might do with gardening tools, or a spear. Abel means breath, or vapor–here for but a moment, then gone.

In time the brothers, Cain and Abel make an offering to God, Cain from his garden, Abel from his livestock. By all accounts God should be predisposed to the firstborn. But, inexplicably, God shows a preference for Abel’s offering.

Cain is the oldest son, so naturally he’s keeping score. Cain’s countenance falls, and he is filled with anger. God sees this and says, “Cain, be careful. Sin is lurking outside your tent. If you do well, then great. If not, sin is ready to devour you.”

Cain says, “Abel, let’s go for a hike,” and within the first mile, it’s done.

Moments later the Lord says, “Cain? Cain, where is your brother Abel?”

“Shouldn’t you know that, God? I mean who died and made me my brother’s keeper?”

“Cain,” said the Lord, “What have you done?”

Cain is silent

“Listen, Cain… Can you hear that? Your brother’s life, his body, his blood? It’s crying out to me from the ground.”

Cain is silent.

“From now on,” says the Lord, “when you work the ground it will not yield to you its strength. It will cry out to you from where it swallowed Abelup, and that cry will be one that you will hear for the rest of your life.”

“No, No, Lord! This is more than I can bear.” Cain says, “I’m just supposed to wander the earth as a fugitive? Who knows what’s out there East of Eden, something, someone could kill me, will kill me.”

“Not so,” says the Lord, “You are mine. No one who harms you will go unharmed,” and the Lord puts a mark on Cain so that no one will kill him. And Cain walks away.

Jesus and most of his friends (who he sometimes calls his brothers and sisters) they knew that story. That’s why they might have leaned in a bit when they heard him tell this one.

There was once a father who had two sons. One day the younger of the two sons came to the father and instead of making an offering, demanded his inheritance early. The father wasn’t close to death, but the young son wanted what he had coming to him now.

The father could have warned his youngest, something like “beware, son, for sin is lurking around your tent,” he doesn’t. He just gives it to him, and off runs the son who just squanders his inheritance on useless things until he’s spent it all and is left destitute. At the end of his rope he’s raising pigs, he decides maybe he could at least get a job tilling and keeping his father’s farm with his older brother.

As he’s crawling back, still a ways off, his father sees him. He up and runs to greet him. And when he gets there, what’s he do? He wraps him up and gives him a big kiss! He doesn’t chastise him, or make him learn a lesson. He doesn’t banish him or make him think about what he’s done. He certainly doesn’t beat him, or kill him. He welcomes him, and offers him as much as he is able to offer.

Meanwhile back on the farm, the eldest son is still out in the cane fields when he hears all the commotion and asks what’s going on. “Your brother is home,” someone tells him. The older brother is shocked. He heads toward the big house and witnesses this welcome home party in full swing. Well, as you can imagine, he’s fit to be tied. He is angry and his countenance falls. Cain had no real cause. This is different.

As he’s stomping toward the party, the father comes out to meet him. The father pleads with him to join the party, reconcile and reunite with his brother. The eldest refuses, saying “I offered you everything, father. For my whole life I’ve been working for you and never asked for anything special! Then here comes this son of yours at the eleventh hour and he’s the one you throw a party for?”

“My son,” the father says, “You have always been with me. Don’t you see? We had to celebrate. Your brother was lost, and now he’s found. He was dead, and now he is alive again.”

Judas would have heard all of this. Judas and Jesus weren’t brothers, but they were close. It was stuff like this that was starting to really get to Judas. This is not the kind of kingdom Judas was looking to enter either. Judas wanted justice. He and his people had been looked over long enough. What he needed wasn’t brotherly love. He wanted a revolution.

You could have said Sin was lurking round his tent. Passover was the last straw, the night they remember a glorious victory over the oppression of Pharaoh and the Egyptians.

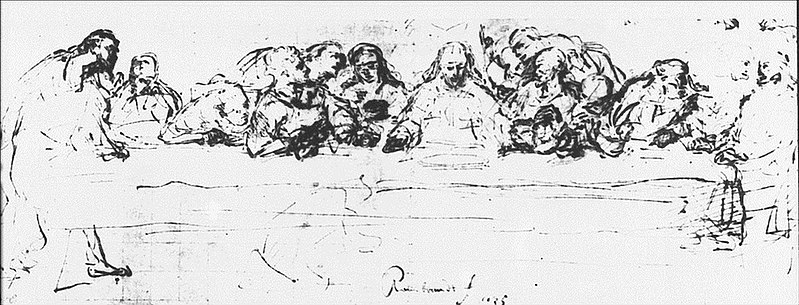

They’re all together at the table, and when they get to the part of the story when the lambs are slaughtered, the last supper before the revolution, Jesus stops everything and lifts up the bread and the cup and says this is my body. This is my blood. What? He’s reenacting a revolution and… he’s… the lamb?

Judas becomes angry. His countenance falls, and he gets up from the table and he stomps out. He goes straight to the religious authorities who are themselves in talks with the Empire. Judas asks for what’s coming to him, and they give him 30 pieces of silver.

Together they go out and meet Jesus in the field and not with a spear, but with a brotherly kiss, Judas sends Jesus to the cross. But there, on the cross, rejected by his brethren, Jesus looks not to them, but to God and with the vapor of his last breath Jesus says, “Father, forgive them, they don’t know what they’re doing.” And with that he dies, and his body and his blood go into the ground just like Abel.

You know, when we baptize one another, in a theological sense, we are putting one another into death. It’s not the ground, it’s in water, but it is a symbolic burial. Symbolically we enter the waters of chaos, the wilderness of sin, we are swallowed up in death, like Abel, like Christ.

Similarly communion is a journey into the mystery of death. We remember the story and we accompany one another to the cross. Not our cross, the cross of Christ, who is for us a new kind of Abel, whose blood is also poured out into the ground.

But ultimately, neither of these sacraments allow us to stay buried in death, with our countenances fallen. They all continue as does this story. Together we then follow Christ not only into death but beyond it, where after three days the ground which swallowed Christ along with Abel is opened again and Christ is raised.

Accordingly, when we enter death in baptism it is a baptism into Christ’s death, which for us leads to eternal life. With him we emerge from the waters of chaos to have our lives ordered by him. Not by rage, or jealousy, or sin, or death, but by the forgiveness of his Cross, and the promise of his resurrection.

And when we partake of the bread and the cup, the Body and the Blood, it is not a body of death. It is not Abel’s blood. It is the body and lifeblood of the Risen Christ. The cup of blessing which we bless, it is a sharing in the living body of Christ which is the body not just of Abel’s resurrection but also of Cain’s redemption.

Before he is sent to wander the earth and ponder what he’s done, God marks Cain in some way. We don’t know what way, but it’s some kind of mark to preserve his life. It marks Cain as God’s own, and protects him forever. I lament the fact that the church, over the last 400 years, sinfully used this “mark of Cain” to justify racism and slavery. Such an interpretation could not be further from the truth.

And it could not be more ironic because this mark of Cain which is a reminder of our estrangement unto death has miraculously been replaced in Christ. In Christ, we have been given a different mark.

We are given this mark in our Baptism. I use my thumb and a little bit of the water. And I always do it again at confirmation, on the forehead with oil. On ash Wednesday it’s the dust of the earth mixed with the sweat of our brow which gives us this new mark not of Cain but of Christ. Likewise at communion or at the benediction, many of us (especially former catholics) mark ourselves once again with this other mark.

The mark we’ve been given is the sign of the cross, and in the church it’s given to us over and over and over. Because it speaks a different word than the blood of Abel and signifies an even better promise than the mark of Cain. This is the sign of our reconciliation. It’s a bible word. It’s also a family word. This is the mark of Abel’s resurrection, and Cain’s redemption, and for us Judases, it is a sign that in Christ we are not given one or the other, reconciliation or resurrection, we are given both. It is a sign of the reconciliation of each human life to God, and of the whole human family to one another, in this life, and the next.

Which do you think we need today? Reconciliation or Resurrection? Hear the Good News: All of this. All of this is God’s gift, offered to us without price. Thanks be to God. Amen.